Some background notes on The Black Paintings, which appears in Black Static # 75, and which is available now from http://www.//shop.ttapress.com

Obviously, these notes are pretty spoilerific so make sure you’ve read the story first!

Most of my stories take me a long time to write. I mean a long time. Pages and pages of notes, worked and reworked, cogitated over, abandoned in a huff and then reconsidered days later once I’ve calmed down. I generally don’t like to start writing without a safety net of some kind, so having that essential structure in place feels crucial to me.

Sometimes however, there are the odd few tales that come to me almost fully formed, or appear to. Usually, like The Black Paintings, I look over the notes again and see that it wasn’t entirely the case. This idea led to that idea and it didn’t actually tumble out across the page, all singing, all dancing as I recalled. But some of them are easier that others; the idea evolving, scenes suggesting other scenes, an ending coming into view quickly. The Black Paintings was one of those stories. It probably took about a week from initial idea to completion. It’s still not that fast, but for me, well that is fast.

Looking at my initial notes I started with a setting that appealed to me. Centre Point in central London towers over Tottenham Court Road tube station and Charing Cross Road, and is one of the great pieces of sixties Brutalist architecture. It’s always screamed JG Ballard to me. After it was built by property tycoon Harry Hyams in 1966, it stood empty as he tried unsuccessfully to find a single tenant willing to pay the money to take it on. Protestors moved in briefly to demonstrate against it, but it became known as ‘London’s Empty Skyscraper’.

In 2010 it was bought by a developer and overhauled into luxury apartments, designed with monochrome colour palettes and huge expanses of glass. A one bedroom home will set you back by £1.8 million, while a three bed will cost you £7-8 million. The two storey five bed penthouse comes in at an eye-watering £55 million. Amenities include a first floor swimming pool, a gym, a sauna, residents club and cinema.

The last I read, the developers had given up trying to sell the apartments rather than lower prices. Apart from a few tenants – one two-bedroom apartment was sold to the parents of a Chinese student about to start studying at UCL – much of it again sits empty.

I found this fascinating, and the idea of a man rattling around a luxury tower block which was largely vacant sounded even more Ballardian.

With the notion that I was heading down that route tonally I was on the lookout for characters and an idea that fitted that setting.

Then a couple of nights later I had to get out of bed with a one sentence idea that couldn’t be ignored. It’s basically the first couple of lines of the story:

On the final day of his life, Lucien Halcomb’s cancer began to speak to him.

“Lucien,” it said, with a voice like clotted blood and fevered nights, “I should like to leave you after all of this is over.”

A lot of the story fell into place quite quickly after that.

After a few false starts I settled on a character. Lucien Halcomb. I don’t know about other writers but I have a file in Evernote with a list of names for future stories. Names have to feel right for me, have to suggest certain aspects of character.

Initially Halcomb was going to be a movie director who, aside from being in the final stages of cancer, is overseeing edits of a final film. We would have first met him at London Aquarium, watching an octopus drifting in the water. I wasn’t sure what the point of this was, story-wise so I deleted it and went a different route. It’ll crop up again later. Instead, Halcomb became an artist, long adrift in his own life, living out the last of his days in a tower block similar to Centre Point.

“I’ve watched you, this last year, Lucien,” the cancer said. “You’re fascinating. No great flights of emotion, no great needs, or expectations. A passenger in your own life.”

“That’s because you’re fucking eating me alive. What do you expect?”

“You were a dead man walking long before I infested your cells, Lucien.”

The initial story title, We All Live in an Empty House became the name of one of Halcomb’s art installations, housed at the Tate Modern (another great example of Brutalist architecture) and forming part of a retrospective exhibition of his life’s work.

I liked the idea of Halcomb’s cancer wanting its own autonomy, so I asked myself the usual round of questions until I had something I liked. The host body is failing. Halcomb lacks integrity, the basic emotions, interests or needs that most of us have. But then the next idea was what quickly made everything else fall into place.

His disease makes him seek out other diseases.’

This idea led to a conversation with my other half, Amanda, about different types of disease that Halcomb’s cancer could seek out, and why. It wasn’t weird – Amanda’s used to this sort of thing by now. Google search, I’m not so sure about. Most days there’s probably someone in a Google building somewhere monitoring my search history and hoisting a huge flag over it.

After that the story became focused on one final night for Halcomb, a tour of life’s little pleasures for both Halcomb and the cancer.

“I want this last night to belong to both of us, Lucien.”

An art gallery, a performance of Beethoven’s piano trios and a final stop in Soho for something that basically wrote itself in one charged writing session. I’ll not talk about it here, but suffice to say that excised scene of Halcomb watching the octopus returned in a different form.

There was something else. The story is called The Black Paintings, which of course suggests Goya and the art he applied directly onto the walls of his farmhouse outside Madrid about 200 years ago. Hugely disturbing dark oil paintings of pagan gods feasting on headless carcasses, a billy goat in a cassock before a congregation of witches, a dog up to its neck in a void.

Half a century after Goya’s death, they were stripped out of the farmhouse and now they are housed at Madrid’s Prado museum.

I’d decided that Halcomb, a man with “…no flights of emotion, no great needs or expectations,” had discovered a need for one final artistic expression. After visiting the Black Paintings exhibitions he returns with cancer and a need to create his own masterwork in the perfectly untouched dining room of his apartment.

It felt right to me, for Halcomb to be awed and moved and transformed too late, and for his passivity in life to be punished by a cancer that desires its own autonomy.

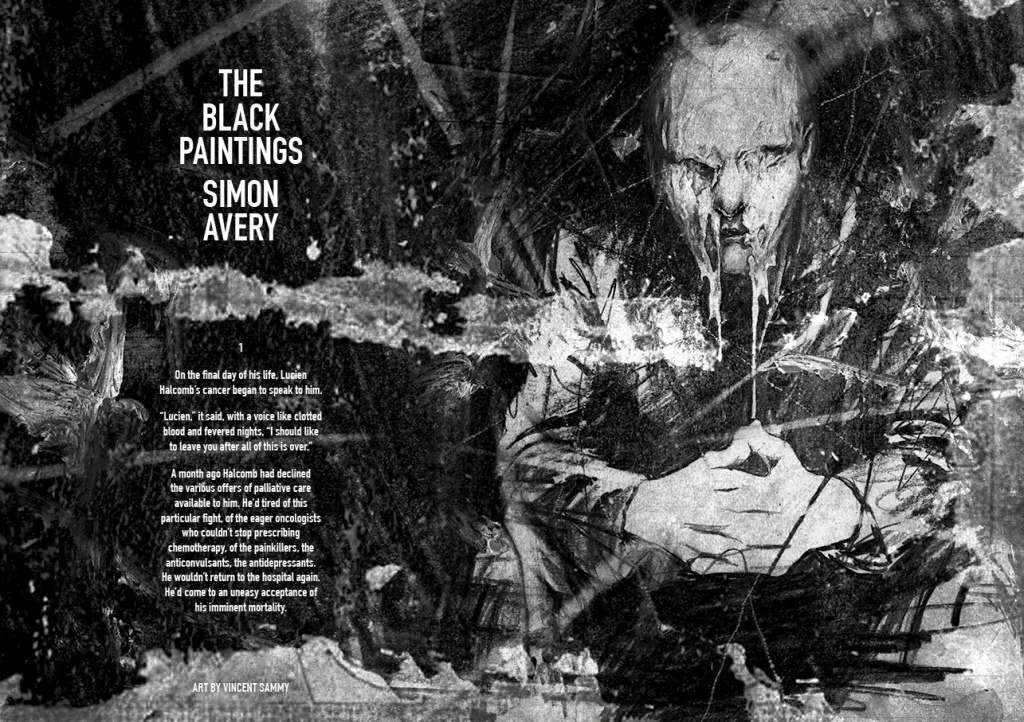

I probably say this every time but one of the great joys of being published by Andy Cox in Black Static is the promise of an accompanying piece of artwork for your story. Andy calls on some spectacular artists for his magazines – George Cotronis, Ben Baldwin, Martin Hanford, Richard Wagner, Vince Haig, to name but a few. This time the illustration for my story came from the ridiculously talented Vincent Sammy. It’s a stunning image. Vincent really went to town with the idea. It’s disturbingly chaotic and positively black with dread. Amazing.

Thanks as usual to Andy for publishing The Black Paintings. He told me he thought it contained one of the darkest scenes he’d ever read, which I’m taking as a compliment. This is my eight appearance in Black Static and my seventeenth TTA Press story overall.

If you can please support Andy by heading over to https://shop.ttapress.com and buying the issue, back issues or even better, subscribing. It ensures the longevity of the small presses for us to keep them afloat in these uncertain times.

As ever, I hope you enjoy the story and please get in touch and let me know if you did.